Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

For decades, blue light was the color physics refused to give us—until one engineer forced a crystal to shine and changed the world overnight.

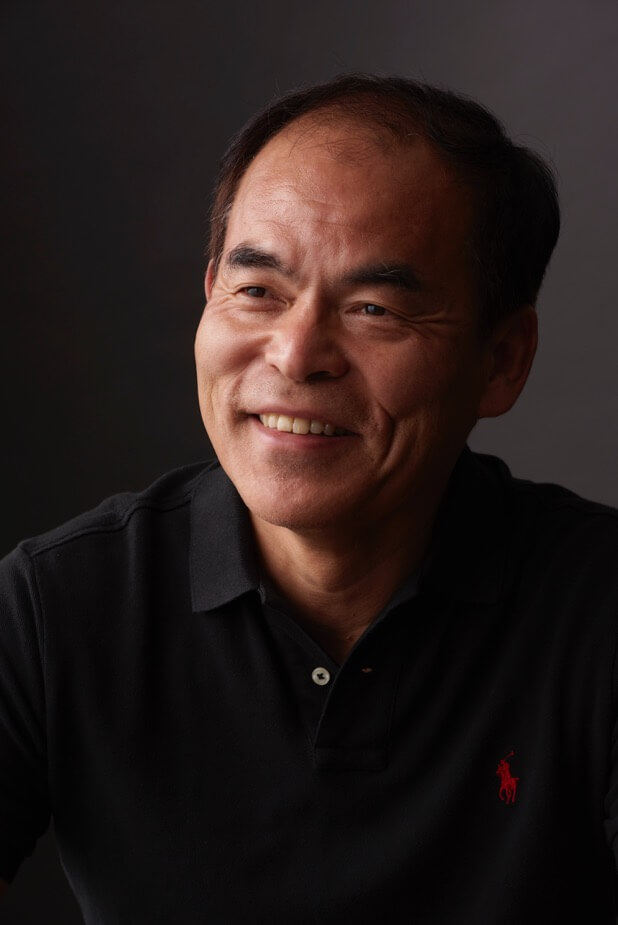

“I never imagined blue LEDs would change the world. I just wanted to prove they were possible.” — Shuji Nakamura.

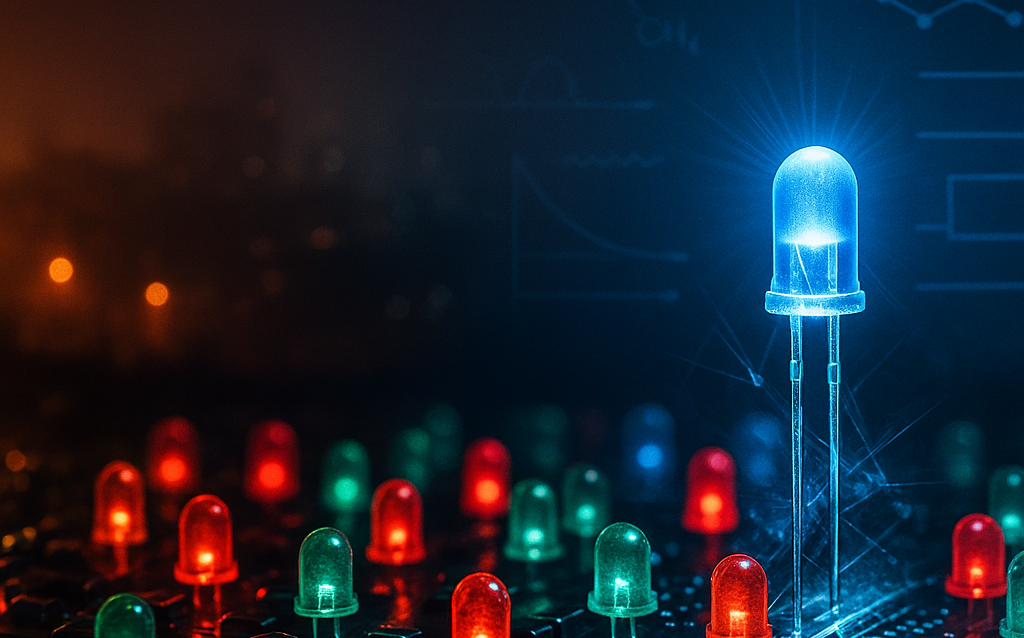

On some evenings, modern cities glow with a cold, steady light. White lamps line the streets. Screens shine in our hands. Tiny indicators blink on our devices. It all feels ordinary now. But this light was once impossible to produce. The blue that sits quietly inside your phone or laptop is the same blue that haunted scientists for more than thirty years.

True blue light did not come easily. Nature gives it to us in the sky and the sea, but technology could not imitate it. We could heat filaments. We could ignite gases. We could even shape glass tubes into glowing signs. Yet none of these methods could create a stable blue from a solid crystal. Not in a tiny device. Not with electricity alone.

That missing color held the entire LED revolution hostage. Red LEDs had existed since 1962. Green followed not long after. But without blue, engineers could not mix the full spectrum. They could not build white LED lamps. And without those lamps, the energy-saving transformation of the modern world would never happen.

To understand why blue was so hard, we must step inside the physics of the LED itself.

Light from an LED comes from a simple but powerful process. Inside the semiconductor, electrons sit in energy levels called bands. When an electron falls from a higher band into a lower one, it releases a photon. The energy of that photon depends on the size of the gap between the bands, which we call the band gap.

A small band gap gives red. A medium one gives green. But blue requires a far larger gap. Only a few materials can provide it, and one of them is gallium nitride, or GaN.

GaN looked perfect on paper. In reality, it was extremely difficult to handle. When grown on a surface, it cracked from stress. It formed rough, uneven layers. It contained many defects that trapped electrons and prevented light from escaping. Each attempt looked promising at first and then collapsed under microscopic examination.

Scientists tried new temperatures, new chemicals, new substrates. They adjusted growth rates. They redesigned furnaces. They wrote hundreds of research papers. But the results stayed the same.

By the late 1980s, the field had grown quiet. Large companies stopped funding the work. Researchers moved on to other problems. Blue LEDs became a scientific dead end—a dream postponed by a stubborn material.

Then, in a small laboratory in rural Japan, an engineer refused to let the dream die.

Shuji Nakamura did not come from a world of prestige. He did not lead a large team. His lab equipment was often built by hand. But his curiosity and determination pushed him forward.

Nakamura used a technique called MOCVD—metal-organic chemical vapor deposition—to grow GaN layers. In most reactors, the gases mixed too soon. They reacted in mid-air and formed a powder instead of a crystal. This powder drifted away, leaving the wafer nearly bare. The results were always poor.

Nakamura changed the way the reactor breathed. He added a second flow of inert gas that pushed the reactive gases downward, preventing them from colliding early. This small change had a huge effect. The GaN layers grew slowly and smoothly. Their defects dropped sharply. The material began to conduct electrons with much greater freedom. For the first time, GaN looked healthy.

Still, this was not enough. Even high-quality GaN needed to be grown in two types: n-type, which has extra electrons, and p-type, which carries positive “holes.” Engineers already knew how to make n-type GaN. But p-type GaN had been impossible for two decades.

Many groups tried to create p-type GaN with magnesium. In theory, magnesium should add holes to the crystal. But every experiment failed. The holes were never free enough to carry charge. The material stayed stubbornly inactive.

Nakamura studied the chemistry more deeply. He found the hidden culprit: hydrogen. During the growth process, hydrogen from ammonia gas bonded to the magnesium atoms. It neutralized them. It locked the holes in place and prevented them from moving.

The solution was surprisingly simple. Heat the crystal. By annealing GaN at the right temperature, the hydrogen atoms escaped. Once they were gone, the holes were free, and the material finally became true p-type GaN.

This single discovery changed everything. A twenty-year barrier vanished. The path to a real blue LED was now open.

With both n-type and p-type GaN ready, Nakamura built a complete LED structure. But he still needed a way to tune the color and increase efficiency. He turned to indium gallium nitride, or InGaN. By adding a thin layer of InGaN between layers of GaN, he created a quantum well. Inside this well, electrons and holes were trapped close to each other. When they met, they released bright light.

Even small changes in indium concentration adjusted the band gap. With careful tuning, Nakamura created a deep blue light at about 450 nanometers. It was bright. It was sharp. And it was unlike anything the world had seen.

Yet there was one more problem. Some electrons escaped from the quantum well and wandered into the outer layers. To stop this leak, Nakamura added barriers made of aluminum gallium nitride. These layers held the electrons in place. The device became brighter and more efficient.

At last, a true blue LED existed. It was stable. It was bright. And it was ready for use in real products.

Once engineers had blue LEDs, they could finally make white LEDs. They coated the blue device with a yellow phosphor. The mix of blue and yellow produced clean white light. This simple trick opened the door to a new age of lighting.

LEDs soon replaced incandescent bulbs, which wasted most of their energy as heat. They replaced fluorescent lamps, which relied on toxic mercury. LEDs used far less electricity. They lasted longer. They produced almost no heat. They were safer, cleaner, and more efficient.

The world’s lighting changed quickly. Cities shifted from orange streetlights to crisp LED illumination. Homes used less energy. Screens became thinner and brighter. Entire industries reorganized around this new source of light.

Blue LEDs made the modern world possible.

In 2014, the Nobel Prize in Physics honored Shuji Nakamura, Isamu Akasaki, and Hiroshi Amano for their contributions to GaN and blue LEDs. The prize recognized more than a scientific achievement. It recognized a transformation of daily life.

You can see their impact everywhere. In phones. In televisions. In cars. In medical tools. In satellites. In the glow of almost every modern device.

The blue LED was once considered impossible. Today it shines around the planet. Every time you turn on a white LED lamp, you see the result of one scientist’s persistence—the belief that even the most difficult problems can be solved.

Nobel Prize overview of the blue LED discovery:

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2014/summary/

History and background of blue LEDs (Wikipedia overview)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_LED

IEEE Spectrum article on how blue LEDs changed the world

https://spectrum.ieee.org/blue-leds-changed-our-world IEEE Spectrum

Hands-on explanation of band gap and LEDs (University of Illinois materials activity)

https://matse1.matse.illinois.edu/sc/f.html M